After all, every picture is a history of love and hate

when read from the appropriate angle.

–Leopoldo Salas-Nicanor, Espejo de las artes, 1731

I’ve been spending time lately with an interesting book — drinking in one chapter at a time some nights just before turning in for sleep.

Reading Pictures by Alberto Manguel explores the various ways human beings “read” images and breaks the viewing process (“seeing”) into a series of imaginative permutations. Although I wonder if these categories could be applied to most if not all visual imagery, Manguel limits his analysis to the fine arts — specifically painting, photography, sculpture, and architecture.

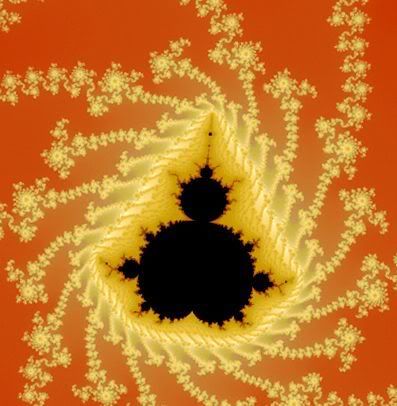

I’m not saying I agree with Manguel’s subdivisions, nor do I mean to suggest that alternative ways of reading/seeing images are not possible. I am interested, however, in trying to determine if Manguel’s rubric can be applied to fractal art — which, naturally, I consider a bona fide fine art.

I’ve chosen my own work to illustrate this first post — because, well, I’m most familiar with it — but, if I continue to post on Manguel’s categorizations, I’ll mix in work by other fractal artists as well.

Here, then, according to Manguel, are the first two options for seeing and reading (and thus interpreting?) any image.

~/~

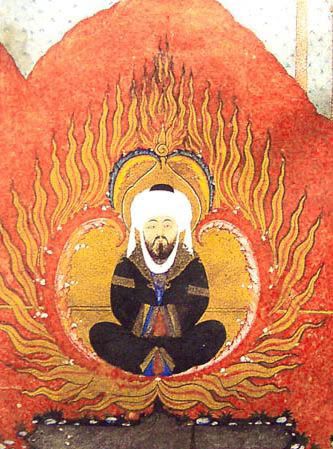

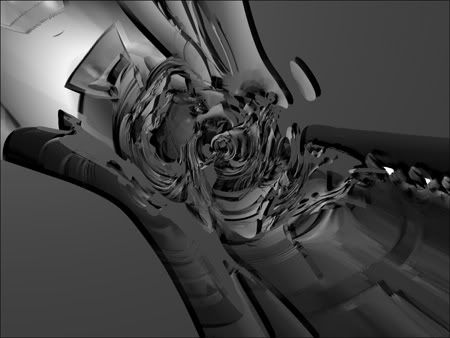

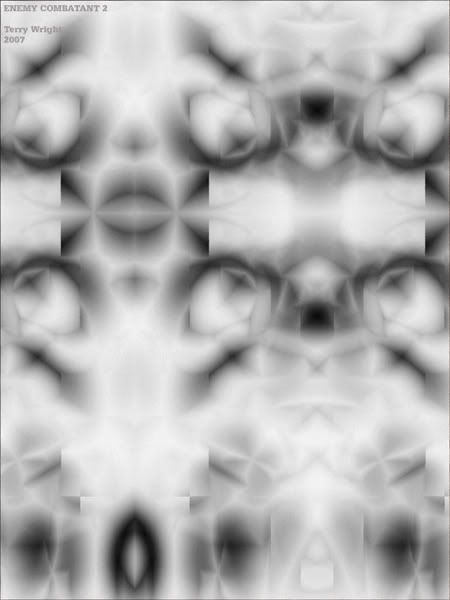

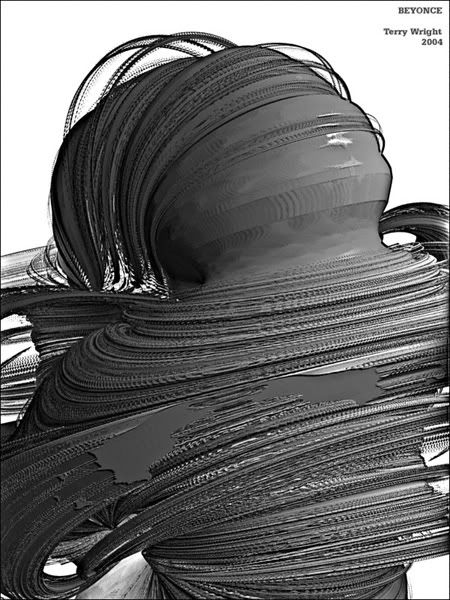

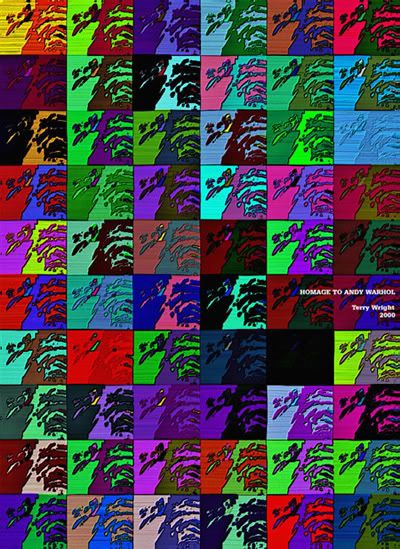

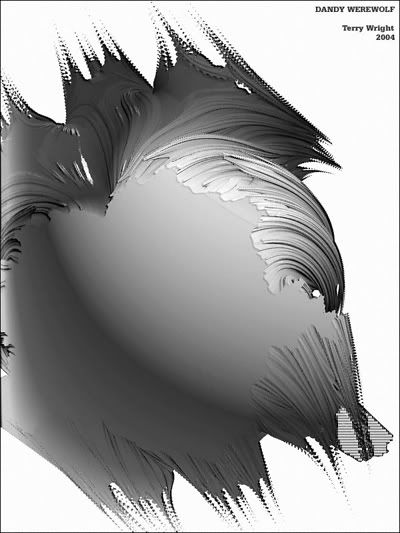

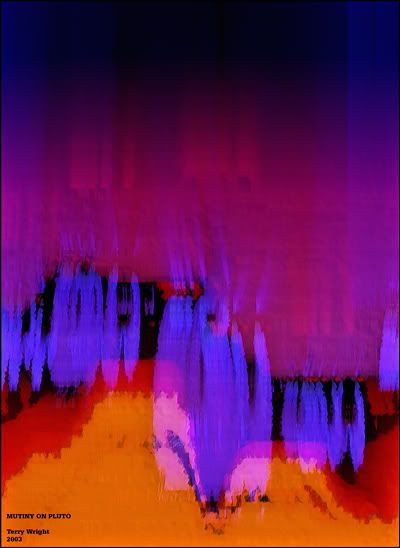

The Image as Story

Every good story is of course both a picture and an idea, and the more they are interfused the better the problem is solved.

—Henry James, Guy de Maupassant

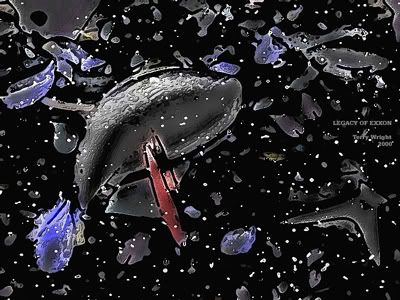

Flower Girl (2007)

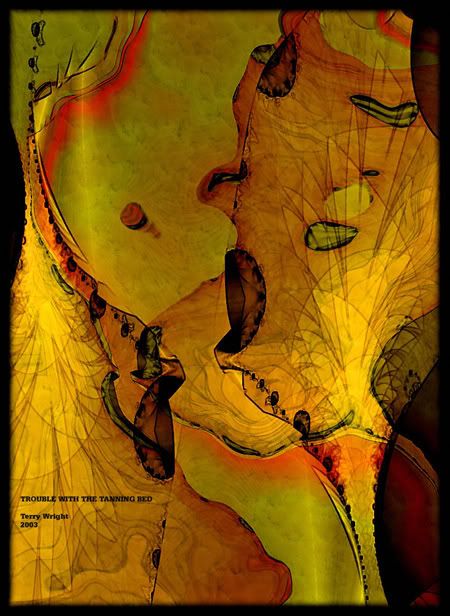

Trouble with the Tanning Bed (2003)

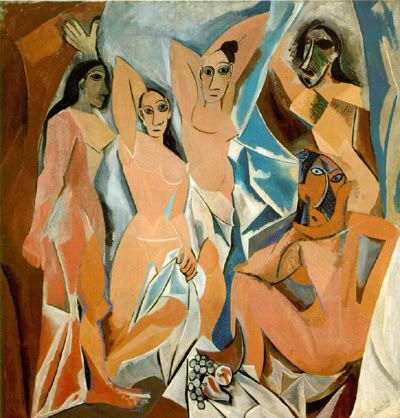

Images are most frequently seen placed within a narrative framework. Not surprisingly, many viewers are driven to “make sense” of what they see — even if the image is highly abstract. The question then isn’t what is it? — but what’s happening here? The answer often comes in the form of a story provided by the viewer — created out of individual experience or pieced together in the imagination. By casting images into narratives, people make pictures meaningful. Fractal artists who make more “representational” art might have an edge here. Manguel notes such story conversion is the most frequent method for “reading” images, and he describes such interpreters as “common viewers.” The example Manguel uses to illustrate this method is Van Gogh’s Shipping Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why some viewers strongly dislike modern art. The abstractions “don’t look like anything.” There’s no nature to mirror and — critical to Manguel — no story to spin.

But wait. Whose story is being told? The artist’s? Or, more likely, the viewer’s? After all, it is he or she who fills in the plot’s missing gaps and supplies the rising and falling action?

And, more disconcerting, can we trust the artist to truthfully tell “a story”? We know novelists sometimes revert to unreliable narrators (like Huck Finn). Film, too, can cause us to distrust the storyteller — as in The Usual Suspects and Memento. How can we be sure the artist is not just messing with us, stringing us along, even mocking us? I’m reminded of Hamlet teasing foolish Polonius over the shape of a cloud:

Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that is almost in the shape of a camel?

Polonius: By th’ Mass, and ’tis like a camel indeed.

Hamlet: Me thinks it’s like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale.

Polonius: Very like a whale.

–Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

Of course, Polonius thinks Hamlet is mad. But what is our excuse if an artist decides we need to be put in our places with ironic jokes at our own expense?

Even if an artist is straightforward, can we always believe our eyes and be certain our concocted stories are not self-deception? Are we seeing only the shadows on the wall of Plato’s cave? Can we “mis-read” an image? And why, even when we’ve studied the same work, are our separate narratives often so noticeably different? Consider this exchange from Woody Allen’s Manhattan when Isaac and Tracy run into Yale and Mary at the Museum of Modern Art:

Mary: Really, you liked the plexiglass, huh?

Isaac: You didn’t like the plexiglass sculpture either?

Mary: Uh, that’s interesting. No, er, …

Isaac: It was a hell of a lot better than that steel cube. Did you see the steel cube?

Mary: Now that was brilliant to me, absolutely brilliant.

Isaac: The steel cube was brilliant?

Mary: Yes. To me, it was very textural, you know what I mean? It was perfectly integrated, and it had a marvelous kind of negative capability.

Apparently, not all our stories get straight — however much we (artists? viewers?) try.

Manguel notes that “storytelling exists in time, pictures in space.” A text is not contained within the boundaries of book covers. We can cite individual lines of Emily Dickinson and summarize whole novels in a paragraph. Here’s Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in one sentence: “A man turns into a bug and his family and his boss get pissed.” But, in contrast, an image is perceived instantaneously and is confined within the parameters of its frame.

What is “the story” of the flower girl in the image above? Is the scene a wedding or a rehearsal or merely playacting? What is her mood? Scared? Nervous? Bored? Or is it inscrutable? Why the big eyes? Where’s the background? Do I see wings? Are the flowers still fresh? Hey. Choose Your Own Adventure.

And what exactly is the trouble with the tanning bed? Did it malfunction turning someone inside out resulting in mass melanoma (and giving new meaning to someone being “toast”). Could it be (cue sinister Cold War music) sabotage??? Or is the image a projection of the future? A suggestion of exaggerated things to come? Or just the horrific sunburn of the living dead?

You tell me. You’re the one “reading” it. What’s your story?

~/~

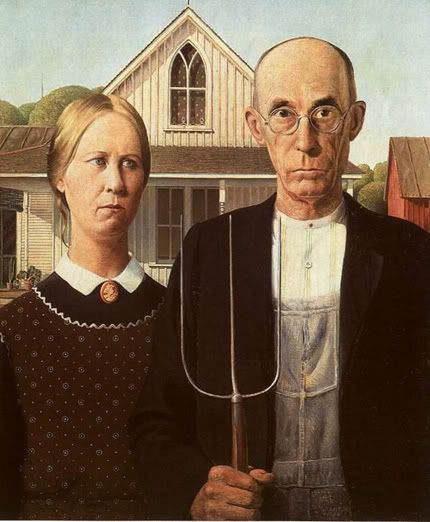

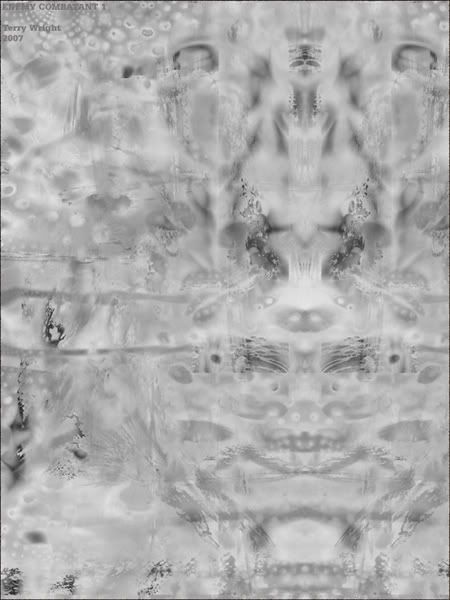

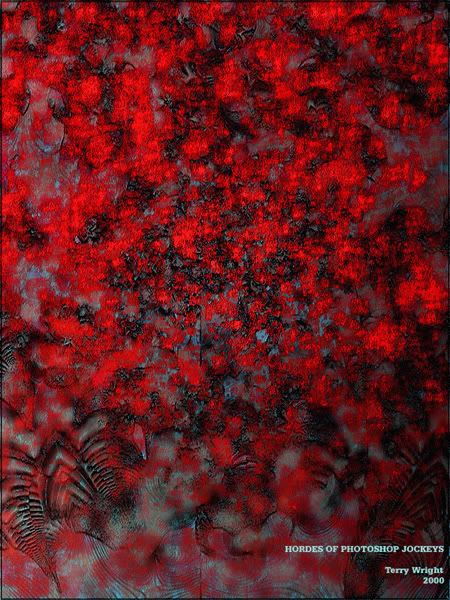

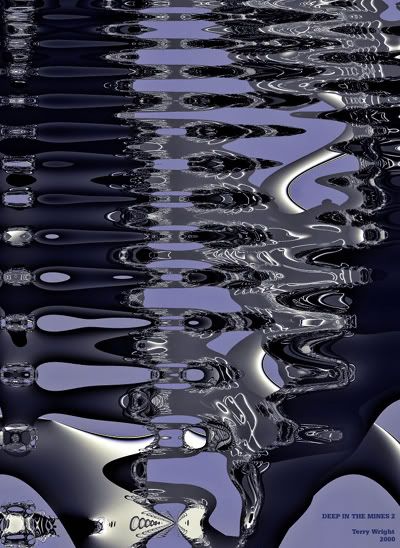

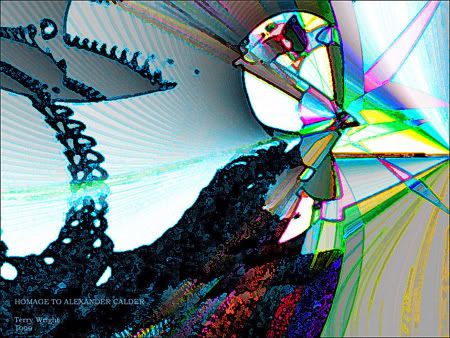

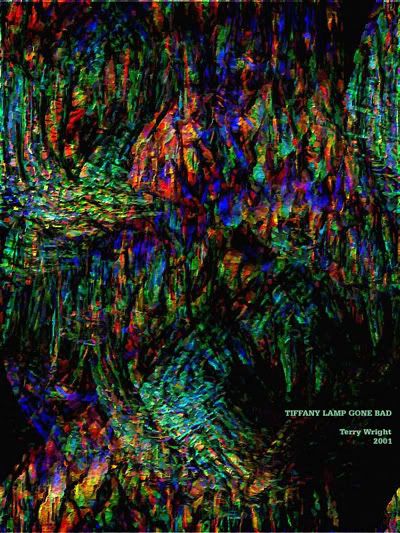

The Image as Absence

To restore silence is the role of objects.

—Samuel Beckett, Molloy

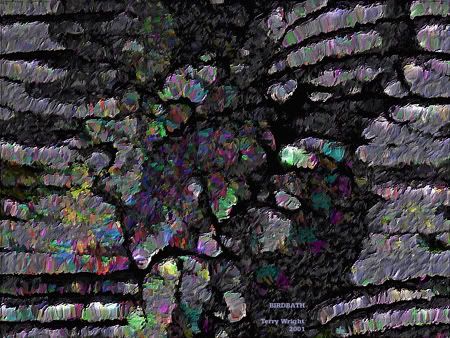

Birdbath (2001)

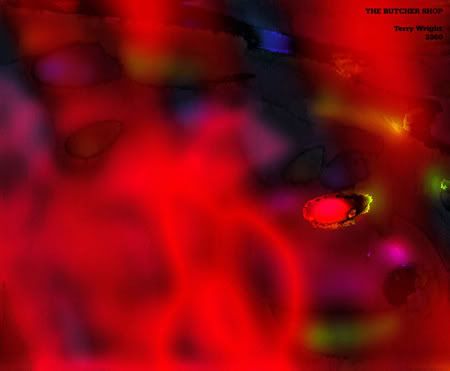

The Butcher Shop (2000)

Sometimes what is unseen is what one is supposed to see. The convenient linearity of the well-made play doesn’t apply here. What is missing is what is meaningful.

Life’s most intense emotional events — like death or divorce — can often be shown better by what is absent: the empty chair at the table, the indentation on one side of the bed, the closet filled with unworn clothes.

How does one see the unseen? Is some art so…I’m searching for the right word here…so…confused…that the very imposition of making a reading undercuts what one is trying to comprehend?

Manguel gives the example of writer Severo Sarduy who wrote about a traveling film projectionist who tried to show a documentary on new agricultural techniques in a remote village in Cuba. The villagers had never seen a film before, and they sat politely on rows of wooden benches and quietly watched the swirling light. Apparently, they recognized a chicken when it suddenly appeared in the lower left corner of the screen — but comprehended little else. They had no way to “read” a film — to decipher its codes of quick cuts and tracking shots. Sarduy sensed the villagers saw the film as a jumble of shadows and light. In short, it was a mess.

Some people had a similar response to the paintings of Jackson Pollock. Just drips. What a mess. I could do that. But at the very moment when the culture was moving away from digesting words (radio) and racing to a constant stream of imagery (TV), Pollock produced paintings that shunned any attempt at narration — either in words or through pictures — and seemed to disdain all control for either the artist or the viewer. Manguel claims that Pollock’s work “seemed to exist in a constant present, as if the explosion of paint on the canvas were always at the point of occurring” (Manguel 24). Maybe that’s why one critic complained that Pollock’s paintings had no beginning or end. Pollock’s reply: “He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but it was. It was a fine compliment” (Manguel 24).

Although Manguel devotes plenty of copy to Pollock in this chapter, he uses Joan Mitchell’s Two Pianos to show work that exhibits absence.

It’s hard to talk about this. Words are one problem here — as Beckett discovered. The more he tried to write about nothingness, the more he had to name it and thus codify it. Colors present a similar paradox. Since every color is named — either individually (“blue”) or in groups (“blue-green”) or in its own subdivisions (turqoise, aquamarine) — Manguel says that no color is “innocent.” Moreover, he observes that colors are not known for their absence — but, instead, for their contrasts. Thus, black is not a vacant void. Rather, it is “not white.” And so on.

So what is absence to the fractal artist? Not a blank canvas. A monitor in sleep mode? The dead space in your generator before you fill it with a fractal? Parameter files riddled with black holes?

Or are those the obvious examples? Elvis Costello once sang: “There are some words they don’t allow to be spoken.” Are there also things we can’t show?

Or do I mean that we can’t know? How much information do we need to properly “read” an image? The artist’s biography? The socio-political context? The deconstruction of all signifiers? An exhaustive itinerary of all materials used? Every trend, movement, and change that impacted the world during the artist’s lifetime? There’s a kind of Howard Hughes obsessiveness creeping in here. I can never wash my hands enough to be completely and perfectly clean. Just as I can never know enough about any given work of art to truly — to perfectly — “read” it. Something will always remain behind a veil.

Balzac wrote about the painter Frenhofer who spent many years fussing over one female nude. The work was to be his masterpiece. He said he wanted to capture that which cannot be captured. “Look,” he said, “there on the cheek, under the eyes, there’s a faint dimness which, if observed in nature, would seem untranslatable to you. Ha! Don’t you think it cost me unspeakable pains to reproduce it?” (Manguel 35-36).

But we’ll never know, will we? Like the Cuban villagers seeing their first movie, Frenhofer shows us something we cannot see because we have neither the language (since it’s untranslatable) nor the context (because it’s unexplainable if seen in nature).

In short, we can never see or read any image in its contextual entirety. Some absence is always going to be a given. Perhaps this is what Beckett meant in Molloy when he said that “there could be no things but nameless things, no names but thingless names.”

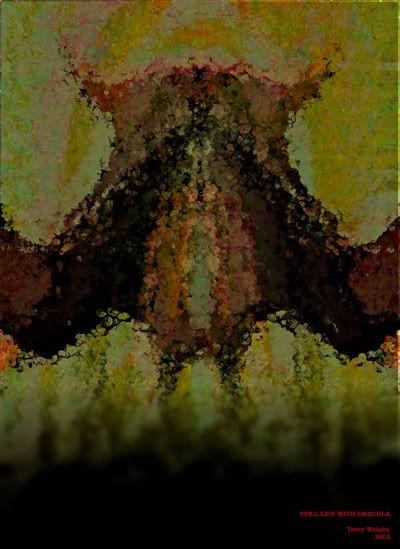

As I was putting the finishing touches on Birdbath above, my daughter, age 13 at the time, walked up behind me and squinted at the monitor. She had a grimace on her face, as if the image had a putrid smell, and the following conversation ensued:

Her: What do you call this?

Me: Birdbath.

Pause.

Her: Where’s the bird?

Me: That’s not the question that bothers me.

Her: What bugs you then?

Pause.

Me: Where’s the birdbath?

The Butcher Shop above looks more like a Christmas card. It has no PETA points to underscore. There’s no cleavers or wooden blocks — no spattered aprons — no blood pools. But something is unseen.

Something remains absent when both the butcher and the artist finish their work. Can you not see…

…not see the animals?

~/~

–Terry

Rooms with a View

Blog with a View

Technorati Tags: fractal, fractal art, digital art, art, reading pictures, alberto manguel, ways of seeing